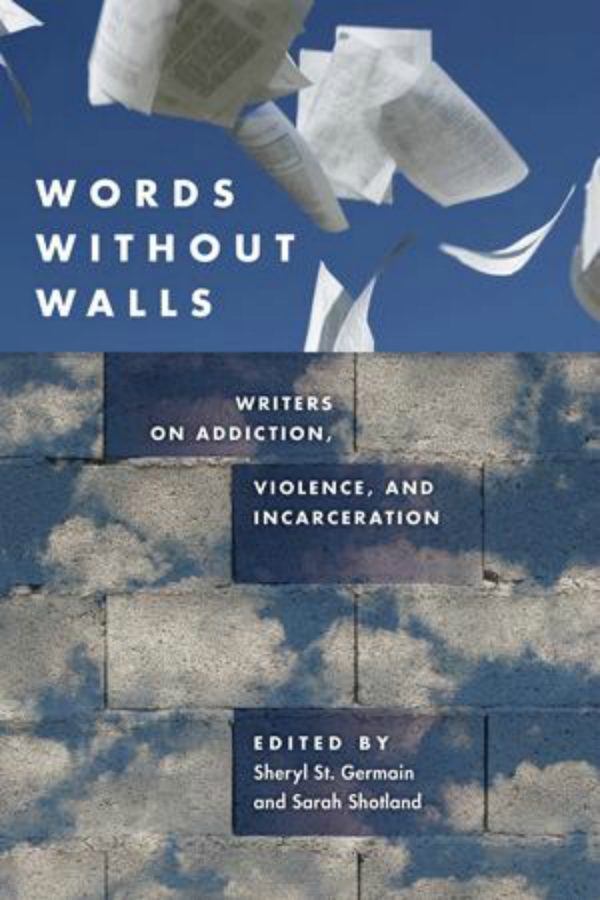

Professors in the MFA Creative Writing Program Sheryl St. Germain and Sarah Shotland have coedited a book entitled “Words Without Walls: Writers on Addiction, Violence, and Incarceration,” now available.

“We wanted works that spoke to experiences we believed would resonate with our audience and that included difficult things—like addiction, incarceration and familial violence,” said St. Germain, who has worked at Chatham since 2005.

In choosing selections for the book, St. Germain looked for, “works that were accessible on a first or second reading, but still offered opportunities for reflection.”

“I tried to pick pieces that were immediately arresting; pieces that grab the reader from the very first line and never let go,” said Shotland, who joined Chatham’s faculty in 2011.

“Words Without Walls” provides perspectives from a broad range of voices, including more widely known authors like Anna Quindlen, Raymond Carver, and Jesmyn Ward—who spoke at Chatham earlier this semester—to those who have personally spent time in prison.

“We wanted a mix of new and respected voices, and we also wanted to honor some of the very best writers from [Allegheny County Jail] and Sojourner House.”

“I tried to pick a range of writers that could begin to represent the diversity of the American experience—in gender, class, ethnicity, geography, and subject matter,” said Shotland.

The book shares its title with the Words Without Walls Program, co-founded by St. Germain and Shotland (when she was a graduate student at Chatham) in 2009, through which Chatham MFA students in Creative Writing teach in the Allegheny County Jail, the State Correctional Institution Pittsburgh, and Sojourner House. St. Germain serves as president to the program, and Shotland serves as program coordinator, and both women teach at Sojourner House (although St. Germain is not teaching this term).

Four pieces included in the book are by Words Without Walls students at Allegheny County Jail and one is from a student at Sojourner House. Work by Words Without Walls teachers Jessica Kinnison and Jen Ashburn and Chatham MFA alum Christine Stroud are included as well. St. Germain and Shotland also have compositions in the book.

Both St. Germain and Shotland have long been passionate about the work that Words Without Walls does.

According to St. Germain, her younger brother spent time in prison as a young adult and, “was taught nothing of value in the prison except how to make art objects with popsicle sticks.”

The two corresponded via letter, and St. Germain was surprised by how well he could write. He died of a drug overdose a few years after being released from prison.

“My initial work with teaching creative writing in prisons stemmed from a desire to reach out to those who might have been like my brother—with some writing skills, but needing nurturance and support,” she said.

During the years between her undergraduate and graduate study, Shotland worked as a teaching artist at a drop-out recovery high school in Austin, Texas, a program she cites as being “enriching and meaningful.” After this experience, she knew she wanted to continue with this kind of work.

“Art at a correctional institution is free from the conventions students learn (and then spend time unlearning) in formal programs. It’s refreshing to be around writers who write because they need to express something deeply important and meaningful, rather than writing with professional goals in mind,” said Shotland.

She continued. “I have professional goals for my writing…so I want to make it clear there’s nothing wrong with professional goals. But it’s important to remember that we create art because it’s necessary for ourselves and our readers and our culture; and hopefully we would continue to do that with or without a prestigious publication or paycheck. Working at the jail reminds me of the necessity of art.”

It is the necessity of art that makes the publication of “Words Without Walls,” which gives voice to a range of authors with a range of things to say, pertinent.

“When our students get up to read their work for each other, their hands are shaking, their voices quiver,” Shotland said. “These are people who have witnessed extreme violence, who sometimes participated in it. It’s sometimes surprising to see how nervous they are at a poetry reading. But it speaks to the fact that these poems, these stories, they matter. A lot.”