Anyone having suffered through holiday dinners understands the chaotic family dynamic. The stories coming from these events become the subject of bragging contests, outdoing friends and peers in terms of ridiculousness. What these stories neglect to mention are how the actions of this dynamic shape individual characteristics.

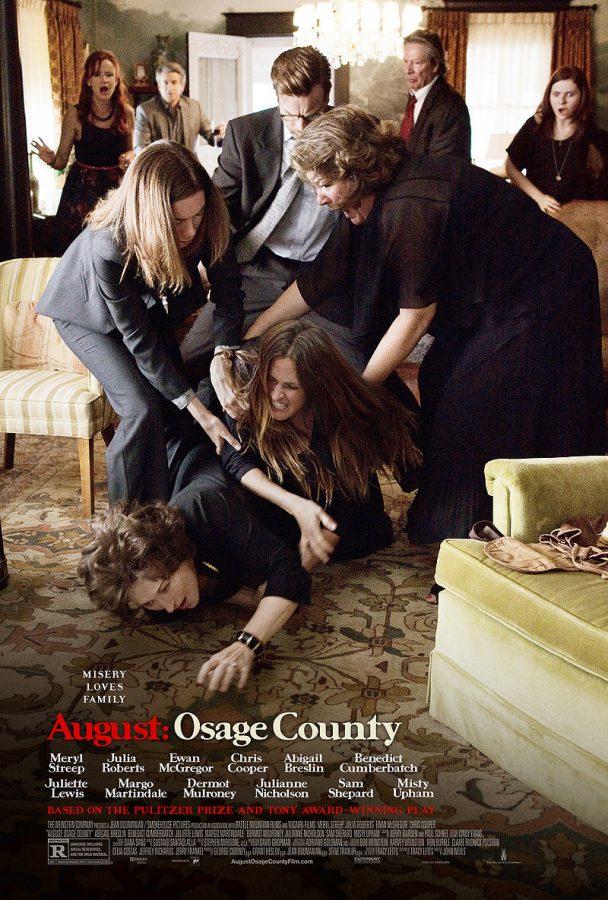

Such tensions play out in John Wells’ film “August: Osage County”. The film centers on matriarch Violet Weston (Meryl Streep) who invites her family over to her house following the disappearance of her husband (Sam Shepard). As the reunion dissolves, the film portrays character sketches of several family members, including the eldest child Barbara (Julia Roberts). Through cinematography, acting, and dialogue, “August” offers a perspective into the family dynamic that becomes both uncomfortable and familiar to watch.

“August” is based on a play written by playwright Tracy Letts. The play became known for its darkly realistic themes concerning family relationships and generational gaps. Letts returned to Osage County as a screenwriter for the film adaptation. As a result of her involvement, the film adapts theatrical characteristics.

One noticeable characteristic is its location. Like setting in a play, Osage County functions as an independent character. Its isolated and rustic nature parallels the larger fragmentation of the Weston family. Cinematography accentuates these parallels through the use of the tight and long shots.

When framing the Weston household, the film utilizes tight shots, which contain the audience in the claustrophobic space, leaving them vulnerable to the events revealed on screen. These shots also pay particular attention to the fence surrounding the house, quarantining the family within its mental and physical space. This containment reflects the predicament of the Weston family, most unable to break away from the barrier of Osage County.

Dialogue further exposes the theatrical background of “August”. Letts carefully laces her exposition through singular lines of dialogue, giving audiences as much information as needed to comprehend the underlying tension surrounding individual family members.

For a film based on growing tension, too much exposition would serve to drag the pacing. The most prominent example of this brilliant dialogue occurs during the dinner scene in the middle of the film. The fluid transition from hilarity to sorrow to rage remind audiences—perhaps too closely—of similar family dinners they have experienced.

Even the assembly of characters such as the naïve Karen (Juliette Lewis) or the disengaged Jean (Abigail Breslin) could be members of our own family. Streep’s stunning performance of a crazed mother using victimization to manipulate her children only adds to the relatable nature of the Weston family. Combined with the vulnerable cinematography, the violent end to the dinner scene seems both natural and disturbingly familiar.

There are moments where these theatrical characteristics slightly weaken the film. People who prefer action to tension will feel the film dragging in terms of pacing, especially without clear resolution. In addition, some characters appear not to be fleshed thoroughly, such as Jean or Johnna, the Native American caretaker for Violet. Their roles in key plot points suggest they had larger roles in the play, but were cut in the film adaptation.

And even though Meryl Streep delivers an extraordinary performance, the same cannot be said for other veteran actors. The one to point out would be Juliette Lewis, who seems out of place playing the child oblivious to her family’s drama.

Thankfully, these bumps do not ruin the emotional power of the film. Though snubbed for a Best Picture nomination, “August” is one of the better movies of last year. The film combines the fear and nostalgia of looking at a photo album, showing us how far we have come and where we still need to go.

Rating: 4 out of 5