When Tony McAleer was at the height of his infamy in the ‘90s, a California-based radio station arranged to take McAleer to Auschwitz for a special live show. When his plane landed, McAleer was detained, interrogated and thrown on the next plane back to America.

The reason: McAleer was a vocal white supremacist and Holocaust denier.

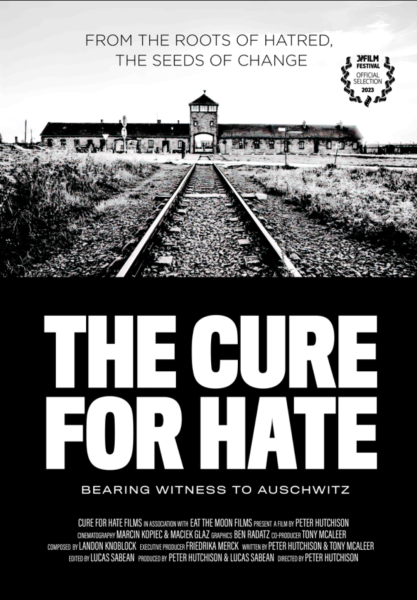

Nearly two decades later, McAleer finally visited Auschwitz, this time as an anti-hate advocate and co-founder of Life After Hate, an organization dedicated to helping people leave white supremacy behind. McAleer’s experience in Auschwitz was filmed for the new documentary “The Cure for Hate,” which is being shown at 6 p.m. on Sept. 27 at Eddy Theater on Chatham University’s Shadyside campus.

Director Peter Hutchison and McAleer took careful measures so that McAleer’s story would not overshadow the tragedy of the Holocaust. Instead, they wanted it to serve as an explanation for how the Holocaust happened.

McAleer explained that his story makes it relevant to younger generations, citing a study conducted by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany that found that 41% of American adults and 66% of millennials did not know Auschwitz was a concentration camp.

“As the last of the survivors pass from this life, it will no longer be in living memory,” he said. “If I’m not part of the film then it’s just looking at a bunch of black and white footage from ‘The Before Time’ and young people can’t connect to it the same way. That was the sort of challenge to film this. How do we tell it through me without making it about me? Auschwitz is the story.”

But McAleer can’t seem to escape his own story. Throughout the interview, he needed little prompting to discuss the horrific consequences of his actions and life of hate.

McAleer’s descent into white supremacy has its roots in his childhood. McAleer traces his violent past to a moment as a young boy when he walked in on his father with another woman.

“I became angry, confused—that shame and guilt like it was somehow my fault,” he said. “At that point, I started to lose trust in all the adult authority figures in my life.”

His grades, once all As and Bs, took a steady dip. His Catholic school teacher would physically harm him as punishment. This, he said, is where he learned to feel ashamed and powerless. He spent years trying to reclaim that power through violence and hateful rhetoric.

After being sent to a boarding school in England, a teenage McAleer discovered the punk scene and quickly fell in with skinheads — a shaved-head punk subculture that often paired with white supremacist and Nazi ideologies.

“I learned to exercise power through people,” he said. “If a neo-Nazi group goes and says, ‘We’re going to be on the street corner, Saturday afternoon at 2 o’clock,’ the violence will come to them. It’s not hard to find that violence.”

In the ‘90s, McAleer became increasingly well known for being, as he put it, a “a big fish in a small pond” intellectually as he donned a suit and became a public speaker for white supremacists, even running a white supremacist phone line.

So how did McAleer go from beating people up on the street corner to visiting Auschwitz as a repentant anti-hate advocate? He held his newborn daughter for the first time in 1991.

“I remember holding my daughter in the delivery room for the very first time, and she’s tiny and I’m terrified,” he said. “I’m thinking, ‘She’s so fragile. I’m going to do something wrong, and I might accidentally hurt her.’”

After a life of feeling unlovable and seeking power and community in white supremacy, McAleer said, he connected to his daughter and began to think of someone other than himself. He had a son a year later.

The children’s mother left the country a few years later, leaving McAleer to raise them alone. McAleer looked to his own mother for help, but she refused to help him unless he cut ties with white supremacist groups.

At this point in the interview, McAleer could have easily glossed over the difficulty of that dissociation and waxed poetic about effortlessly leaving a life of hate behind. Instead, he leaned into self-reflection. Leaving the movement did not make him a better person, he said.

“I never dealt with any of the stuff that made the movement attractive to me in the first place. So, I was still angry. I still had an angry edge,” he said. “While it had been a long, long time since I was involved in violence, my ability to hurt people verbally with sarcasm, humor, wit and humiliation was still present. I was still a jerk.”

What made him a better person, he said, was years of counseling — by his count, over a thousand hours. In 2011, he co-founded Life After Hate with Sammy Rangel, Angela King, Arno Michaelis, Christian Picciolini and Frank Meeink to help other “formers,” people who have left white supremacist and alt-right groups.

By the time McAleer made the trip to Auschwitz in 2018, he had been out of the movement for nearly two decades.

“The Cure for Hate” premiered in Pittsburgh at the JFilm Festival in April. Debuting in Pittsburgh the same year as the Pittsburgh synagogue shooter went on trial for killing 11 worshippers in the Tree of Life synagogue was no coincidence, according to McAleer.

“White supremacist ideology, neo-Nazi ideology, if left unchecked, always ends in murder,” he said. “It’s so important that we enter this realm with a serious intent, and there’s no better place to really kick off our educational program, which we’re doing this fall, than to do it here in Pittsburgh. It has so much significance in the struggle against hatred and antisemitism.”

McAleer still has faith that anyone can turn away from a life of hate like he did. After the shooting, McAleer had the opportunity to visit the Tree of Life synagogue and speak with Rabbi Hazzan Jeffrey Myers and survivors.

“The compassion that was shown to me, knowing where I come from, was a deeply moving experience,” he said. “It’s an incredibly powerful thing to feel it and gives me such great hope for humanity. The purpose of these attacks is to draw the world into more anger, more division and revenge and to be able to resist that and rise above it gives me incredible hope for humanity.”