In honor of Chatham University’s Global Focus year of Southern Africa, students and community members alike gathered in Chatham’s Sanger Hall for a screening of the 1989 film, “A Dry White Season,” sponsored by the Chatham Global Focus program in conjunction with the Sembéne Film Festival.

As attendees ate the pizza provided for the event and waited for it to begin, conversations in a multitude of languages could be heard, giving the the room an air of multiculturalism that lent itself to the theme of the evening.

Shortly after 6:00 p.m., Sabira Bushra, Sembéne Festival Program Coordinator, welcomed everyone and began the event by giving attendees a bit of background and context for the film and the events that it portrayed.

“Euzhan Palcy, the director, was the first black female filmmaker whose movie was ever picked up by a major studio,” Bushra began, adding that they filmed in Zimbabwe and that at times Palcy, “posed as a singer to get all of the content for the film.”

Based on a novel of the same name by recently deceased author André Brink—a white South African who won the Nobel Prize for his book—the film itself was about the aftermath of the Soweto uprising—an event where “students as young as elementary school…spoke out against being forced to use Afrikaans in school,” Bushra explained.

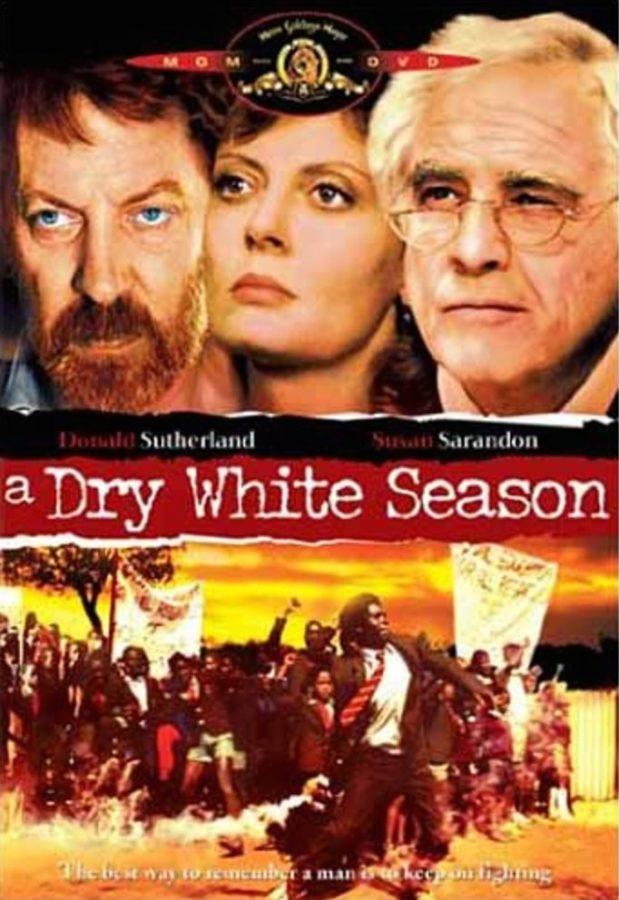

It chronicled the journey of a white South African named Ben Du Toit (Donald Sutherland) who discovers first hand the horrors of the apartheid government—horrors to which he had previously turned a blind eye—when his friend Gordon Ngubene (Winston Ntshona) is tortured and killed by the government for trying to find the location of his son’s body after he was killed by police during the peaceful protest.

As the social justice lawyer (Marlon Brando) that Du Toit hires to represent the Ngubene family says, if justice and law are distant cousins, “here in South Africa they’re simply not on speaking terms at all.”

The film’s blatant anti-apartheid message could not be mistaken, with its powerful dialogue—including lines like, “they closed the eyes of the dead, now the dead will open the eyes of the living”—as well as its graphic depictions of violence and scenes of protests so moving and powerful as to elicit audible gasps from many audience members.

When the film came to a close the room sat in silence for several moments, the only sounds coming from the soulful music playing behind the credits as they scrolled across the screen.

As people slowly recovered from the shock of the final scenes, Dr. Jean-Jacques Sène, Global Focus coordinator, made his way to the front of the room to lead a post-viewing discussion of the film.

After opening a word document of talking points that he wanted to cover, he began the discussion by speaking a little bit about his background—explaining that he grew up and earned his undergraduate degree in Senegal—and admitting that, for him, the film, “hits home in a very particular way.”

He went on to explain that he was assigned to read the book in his freshman year of college, saying, “I was lucky enough that I was exposed to these ideas,” and mentioning how apartheid was, at that time, referred to throughout Africa as, “the apartheid cancer.”

“The book itself was painful,” he continued. “It was written to be painful.”

He further stated that, despite the end of apartheid, “nothing has changed [in South Africa].”

“The current apartheid AMC government is no better than the apartheid government in how they treat black people,” Sène continued. “We have to be in it for the long haul.”

“Hope is not indispensable to audacity,” he continued, closing his comments by posing the question, “how and when shall we globalize human rights?”

Sène then opened the discussion to the audience, at which point Fred Logan an advisor for the Sembéne Film Festival expressed the opinion that the film was “white centric,” as it was, “told from a white perspective.”

He went on to mention that the apartheid government “got its but kicked in Angola in 1988.” He asserted that this was a major factor in the end of apartheid that, “the West does not concede.”

As the audience digested his words and nodded in agreement, Frankie Harris, a woman near the back of the room, entered the conversation with some disturbing insights about the correlations between the events depicted in the film and the state of the United States today.

“This is my reality,” she said, emphasizing each word, and explaining that she has an 11-year-old son who, “can’t walk to the park to play with his friends because the police could stop him and he could end up being another story.”

The other attendees were clearly affected by these words, and sounds of affirmation were heard throughout the room.

She further asserted that the forced removal of black South Africans from their neighborhoods is much like the forced displacement of residence of Pittsburgh’s Hill District.

“We’re talking history that goes back generations,” Harris noted. “And now the gates are being put up…how did humanity get to this point, where we treat each other like this?”

This led to a question of whether or not cruelty is just human nature, but Logan Quickly put an end to that idea, saying, “It’s certain systems that are built on oppression…if you live in an oppressive system, you fall in line with that system.”

In an effort to close the discussion on a somewhat lighter note, Sène rejoined the conversation to say, “The silver lining is, all oppressive systems are temporary.”

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Sène said, quoting Martin Luther King Junior. Then, after a pause he added, “And we are on the good side.”