When my father was 18, he smashed the windshield of his father’s Corvette after a justified spout of built-up frustration and an over-the-top display of anger. Shortly after, he fled his home state of Massachusetts and made his way down to one of Ohio’s many bustling public universities in search of an escape. It is at this school that he credits his time as a newfound individual, and additionally, his ability to release himself from the reins of his past.

Over the summer, only months before entering Chatham University’s campus, I listened to the stories my father slowly revealed to me throughout our dwindling time together, and I was amazed by the thousands of lives that he lived in a matter of three years. He told me about his experiences of living with a pastor, who had taken him in out of genuine kindness. He recalled his time going to wild parties constantly, never enjoying them, and even shared memories of taking refuge in the homes of past girlfriends during holiday breaks. For me, each tale within the endless slew of dramatic young adulthood fostered new levels of admiration and, simultaneously, mediocrity.

The stories of my father’s past have unlocked a constant, nagging yearning to be as interesting as he is — to reach a level of captivation and ground-breaking rebellion that I set for myself in the wake of his late teens and early 20s. And while I see occasional bits of his collegiate self reflected in my current state: his introverted tendencies, facial piercings and almost criminal independence, I find myself feeling like a shell of the person that he was.

My weekends are not the crazy back-to-back raves that I anticipated. I have not been able to let go of the ghosts of my past and I’ve failed to completely reinvent myself. Even more disappointingly, I have not stumbled upon my “calling,” and I’ve come to realize that a “calling” is nothing more than an emotional inclination coupled with an innate skill that coincidentally points in the same direction. However, my all-consuming desire for the experience of a lifetime has led me to one conclusion — a lesson my father would later tell me.

It’s okay to be ordinary.

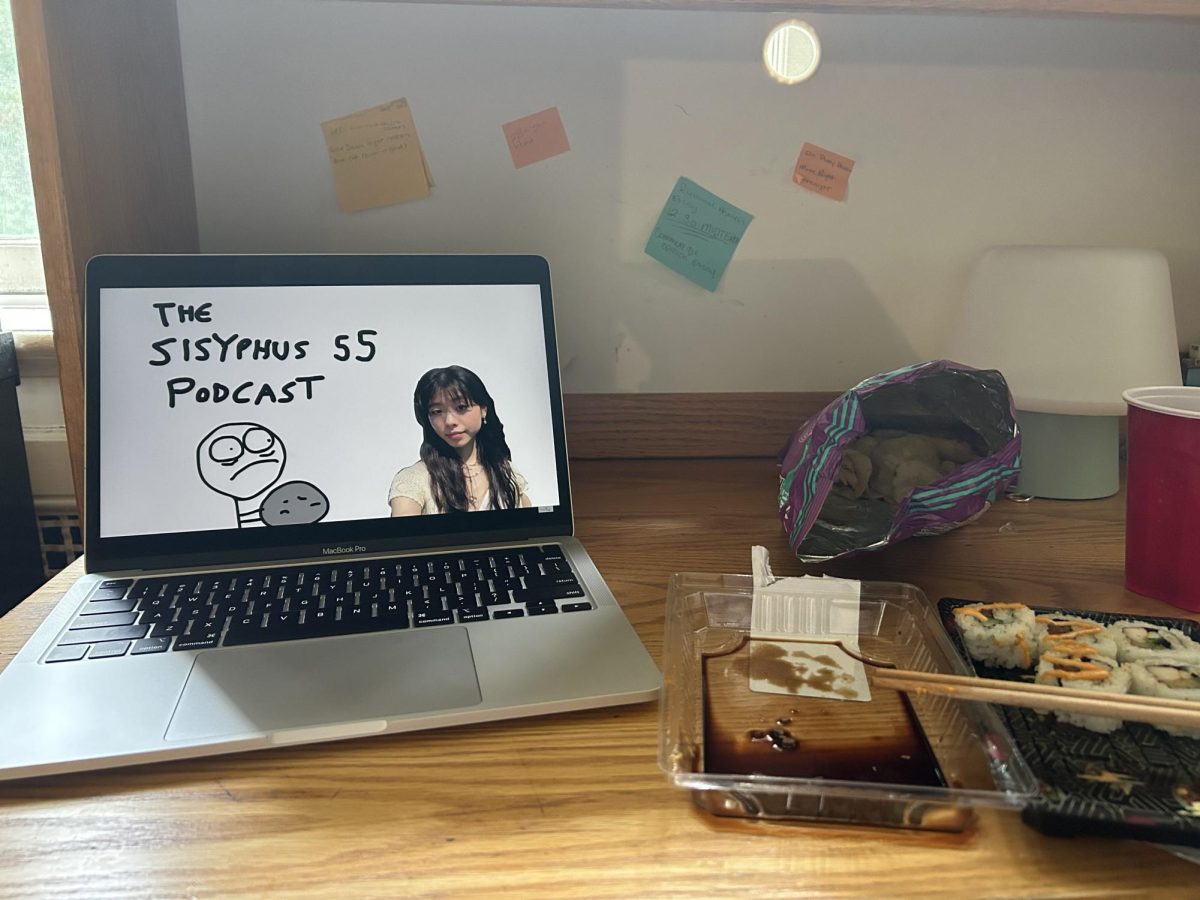

The vision of my extraordinary, fantastical lifestyle dwindles as time passes, and the chaotic adventures I turned to for joy are replaced by slight nuances between repetitive weekly cycles. Hopes of quickly developing friendships turn into shy slow burns between classmates and Saturdays spent wandering nearby campuses with my roommate are now rewatches of “The Notebook” accompanied by buffets of Chinese food on our dorm room floor. As I’ve learned recently, contentment is only possible when personal acceptance is, too, and that means being okay with being boring.

In my limited number of weeks as a college student, I’ve started to learn that stressful weekday schedules can be relieved with nights of rest instead of social events and that happiness is not provided by the situations you’re in, but what you’re willing to find it in. My first term of freedom has allowed me to understand that the point of college, and life, should not be to create a riveting story, but a fulfilling reality, despite the desire for something more glamorous.