Physical space in film functions as a tool of emotional manipulation. These spaces allow the characters to express themselves independent of reinforced societal boundaries. Success of these spaces relies on the film’s ability to enclose audiences within that space and have them experience the same emotional tumult as that of the characters. Director Jason Reitman attempts this with his new film “Labor Day”.

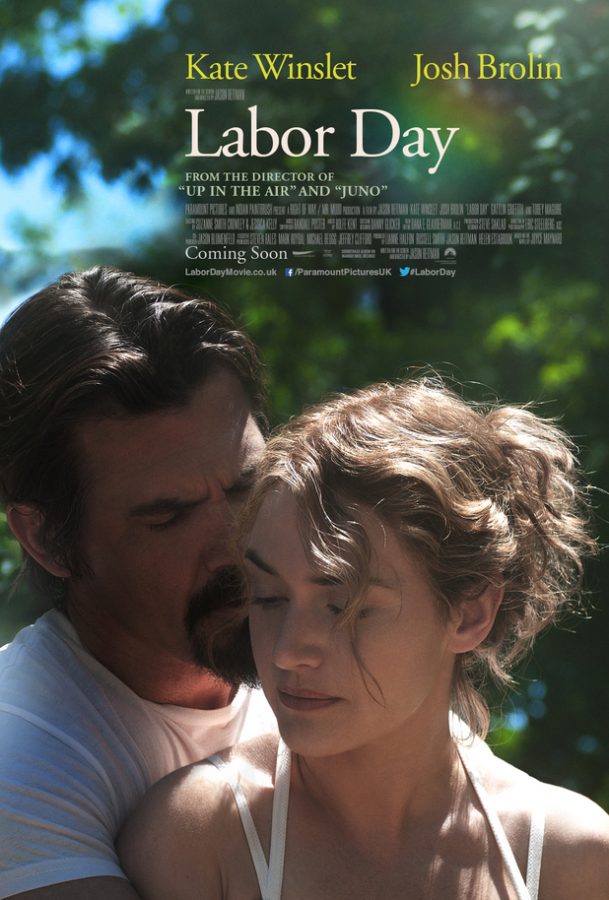

Lonely teenager Henry (Gattlin Griffith) lives with his newly divorced mother, Adele (Kate Winslett) at the edge of a suburban town. Their isolated lives become shaken when escaped convict Frank (Josh Brolin) hides out at their house to avoid the police. As Henry watches love blossom between Adele and Frank, he learns the importance of sex, family, and passion. Despite beginning effort, disjointed narrative elements weaken the power of the space, causing problematic moments in the film. The so-called ‘happy ending’ reigns dominant in the discussion of space.

Reitman establishes space within the first few minutes of the film. Tracking shots lead audiences out of a suburban town and down a long stretch of road, dragging as the houses increasingly become further apart and more dilapidated. These shots slowly transform into tight shots focusing on a house.

The narration of an adult Henry invites audiences into that house, and into the primary space of the film. Henry’s narration demonstrates an incredible vulnerability, drawing in audiences through his poignant observations on his mother’s state of mind following her divorce. This isolation extends into the suburban town. With its central square and grocery store, the town seems to have been taken straight from Updike’s short story “A&P”. The town employs a pastoral feel, making Adele and Henry contagions in this constructed society. By establishing the space, Reitman creates the circumstances necessary for Frank’s entrance.

Paralleling Henry and Adele, society quarantines Frank by having thrown him in prison for the murder of his wife. His isolation is institutional as opposed to the self-isolation of Adele and Henry. The home space allows Frank and Adele to seek solace in their individual isolation. Audiences can develop sympathy for Frank, an acceptance of their love despite literal and metaphorical imprisonment.

Except this sympathy never takes place. The home space falls apart through technical and structural weaknesses of the film. Random plot points arrive but are then never fleshed out. One of these points concerns Henry’s almost Oedipal relationship with his mother. Henry explains through narration that, although he can complete most tasks a husband does for his wife, he could never provide the intimacy his mother ‘required’ in marriage. A follow-up scene later in the film shows a flashback with Adele teaching Henry the emotional power behind making love. Her lascivious pose on the hammock while talking to her son is problematic in its own right, but the movie nevertheless does not resolve this moment.

Another unresolved plot point surrounds Frank’s innocence. Evidence never arises toward his vindication. A moment occurs in the film implying another murder, but the scene quickly jumps forward and is never referred to again. The film expects us to believe in his patriarchal charm. His relationship with Adele demonstrates a ‘sexual awakening’ moment characterizing more conservative gender roles.

Pacing further weakens the film by rushing the ending past these unresolved plot holes. Reitman destroys the original message of his film so Frank and Adele can walk arm and arm into the sunset. The illusion of space disappears in the film and unfortunately never returns.

If you really want to watch films on Stockholm Syndrome, it’s best to stick with the classic. I’m pretty sure “Beauty and the Beast” is on Netflix.

Rating: 2.5 out of 5.