Not too long ago, I reviewed the film “August: Osage County”. It examined the darker elements of one dysfunctional family, its members hopelessly intertwined within its own drama. Although the film offers an accurate portrayal of a dysfunctional family, it is certainly not the only depiction. What happens to families whose members have successfully broken out of the dynamic? How can poignant moments arise from a larger dysfunction?

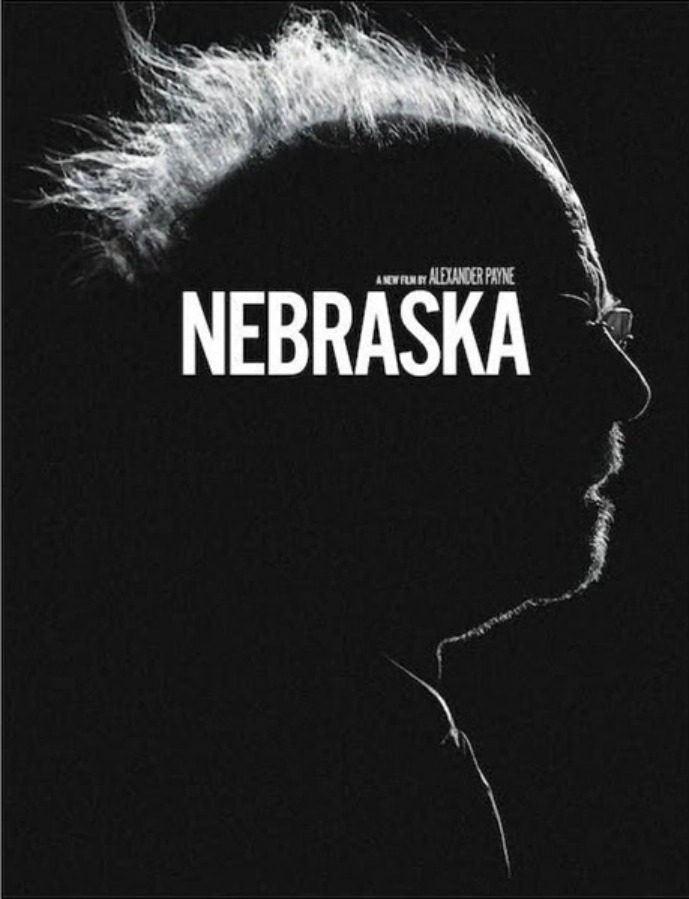

Director Alexander Payne explores these themes in his film “Nebraska”. Senile Woody Grant (Bruce Dern) believes that he has won a million dollars through a publishing clearing house contest. Though his family warns him of the scam, his youngest son David (Will Forte) takes him down to collect his winnings. During this trip, they spend a weekend in Woody’s hometown of Hawthrone, Nebraska. Payne creates a beautiful film that is both family memoir and travel narrative. Technical nuances and surprising acting performances combine to make a compelling story.

At first, “Nebraska” reveals the deceptively simple plot of a half-crazed man trying to secure imaginary winnings. Aggressive family members surrounding him provide the inevitable obstacle of reality. The introduction of David adds more to the mystery behind this film.

Seeing Will Forte in a semi-serious role is rather strange for this “Saturday Night Live” veteran. When David and Woody embark on their journey toward Nebraska, the pacing of the film appears incredibly quick. It draws question of how long the plot can be stretched as the film nears its destination. This mood changes quickly once Woody and David go to Hawthorne. Here, the beauty lies in the details.

The residents carry the small town feel right down to their tailored accents. Though some critics believe these characters to be mocking caricatures, they do not acknowledge Payne’s poignant realism. The provincial accents, newspaper offices run by one person, and hero treatment toward Woody encapsulates the nature of the rustic town. The black and white coloring of the film highlights Hawthorne’s nostalgic and pastoral nature, stranding the town in time. Even Lincoln, Nebraska’s urban center and Woody’s destination, feels otherworldly with its gleaming buildings blurred from the distance.

At one point, David becomes a vessel for audiences to view Woody and the people of Hawthorne. This transition occurs when David sits down with Woody and his brothers to watch the football game. The brothers sit uniformly while David sits noticeably off to the side, the dark color of his flannel contrasting with the brothers’ white clothing. Suddenly, audiences receive participant status in the film.

Audiences engage with Woody’s past, often with humorous anecdotes. The best of these scenes involves David and his brother Ross (Bob Odenkirk) attempting to steal back an air compressor for their father, only to find out they robbed the wrong house.

The overlapping provincial dialogue and wonderful moments of tension give this movie the feel of a travel memoir with David getting to know his father through the culture of Hawthorne. Soon, the film transcends the simple collection of winnings. It analyzes the beautiful disarray of the family dynamic, along with the construction of social realities. Hawthorne acts as both a deindustrialized graveyard of memories and a chance at personal redemption.

The film provides a complexity in its mystery behind Woody Grant. Audiences receive only snippets of Woody’s life, but, like David, we play with this information to understand what goes on behind his seemingly lifeless eyes. It may not pack the same emotional punch of “August”, but it is a punch nonetheless.

Rating: 4.5 out of 5.